The beach will re-open on July 31 after being closed to the public since May due to extensive flooding.

Toronto Island Park, including Hanlan’s Point, will reopen Monday. In his announcement, Mayor John Tory said, “For many Torontonians summer isn’t complete without a visit to the Toronto Islands.” But for the LGBTQ community, this is an understatement. Hanlan’s Point is an historic LGBTQ site and, for our community, visiting it is a time-honoured tradition.

Running down the western coast of Toronto Island Park, Hanlan’s Point Beach has been flooded for most of the summer. Well above average rainfall since early April caused Lake Ontario’s water levels to rise higher than they had in decades, at times putting more than 40 per cent of the Toronto Islands underwater. The average Toronto resident probably found the loss of most of Toronto’s beaches for most of the summer distressing, but there are a few communities for whom Hanlan’s Point Beach is particularly significant.

Hanlan’s Beach is clothing optional. Among the many who enjoy the space, nudists use it to be legally, publicly nude. It’s a place frequented by LGBTQ people, since nudism isn’t inherently sexual. The open-mindedness of a nudist-friendly space makes people of diverse sexual orientations and gender expressions feel welcome and safe.

The use of Hanlan’s Point Beach by those communities, however, is not new.

University of Toronto historian Dale Barbour focuses on the history of bathing: “Think of [Hanlan’s] in the 19th century as being a nude beach. It’s where they kind of push people who wanted to bathe on the island.” Barbour says as customs and clothing inventions changed, Hanlan’s Beach became a clothed space.

In 1880, a Toronto bylaw was passed requiring people to wear bathing dress from the neck to the knees. In 1906, Toronto Police raided the beach, arresting 26 people for improper dress. Barbour says there’s record that the culture of Hanlan’s reverted to a nude space as early as 1950, and by the 1970s, it was known explicitly as a nudity friendly space, regardless of the law.

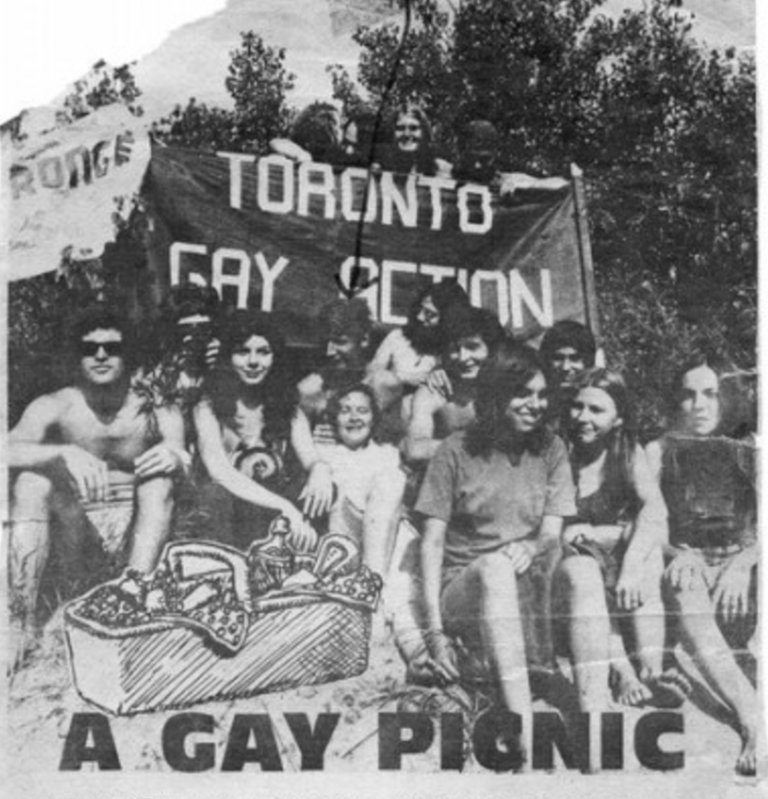

By the 1970s, Hanlan’s Point Beach also became known as a gay-friendly hangout spot, Barbour says. Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau decriminalized homosexuality in 1969. Two years later, on Sunday, August 1, 1971, Toronto Gay Action, the University of Toronto Homophile Association, and the Community Homophile Association of Toronto organized a picnic at Hanlan’s Point Beach called Gay Day.

The Gay Day Picnic is widely believed among activists active at the time to have been the birth of Toronto Pride. Guerrilla Magazine, an activist magazine that circulated in Toronto from 1970 to 1973, reported that 200 to 300 people attended. It was a time of burgeoning gay activism. On the 28th of that same month, We Demand, the first federal gay rights protest in Canada, took place on the steps of Parliament in Ottawa demanding full equality.

Crime journalist James Dubro says he “basically lived” at Hanlan’s in the early 70s. He remembers that bars had arbitrary rules prohibiting people from walking around a bar with a drink in hand. “You had to sit at the tables,” he says. “Hanlan’s point was a place where we could all take our clothes off and be ourselves.”

Dubro contrasts the rigid bar rules of the time with stories of jumping from blanket to blanket, engaging in hedonistic fun. He says the LGBTQ movement was in its infancy at the time, and that their primary concern was visibility—showing larger society that they even existed.

Gay Days were held in 1971, 1972, and 1974, then took a hiatus. In 1981, of course, local gay activism experienced its most pivotal moment in history, when the Toronto Police Service carried out Operation Soap, and raided four gay bathhouses, charging 286 men for being “found-ins.” That event triggered a profound activist backlash, which would fundamentally shape Toronto Pride.

Hanlan’s Point Beach became officially recognized by the City as clothing optional in the year 2002 after the work of Totally Naked Toronto and lawyer Peter Simm. “It’s very important to us as a legacy item, that we provided to the City of Toronto, and we’re proud of it and we like to use it because it was a hard won fight,” says James Forbes, TNT president and events chair. Forbes also notes that Toronto is one of the only cities in the world with an urban clothing-optional beach.

Some members of the community have voiced concern about erosion that has no doubt taken place while the beach was flooded. Head of watershed programs at Toronto and Region Conservation, Nancy Gaffney, says people shouldn’t be too concerned. “There is a pretty good foundation of sand there, so while we may have lost a fair bit of sand, and the beach won’t be as wide as it has been in the past, you’ll see quite a substantial beach left,” she says.

Gaffney says the sandbags used to block water during the most severe flooding period can be emptied to artificially extend the island’s beaches. “I think there’s a lot of mitigation we can do to return those beaches back to as big and as wonderful as they used to be,” she says.

“Beaches change. Beaches are dynamic,” says Forbes. “If there’s any silver lining to this, it shows how fragile the ecosystem is there, and how more development would be a really bad thing. It’s not something that is a given. We have to cherish it and take care of it and protect it,” he says.

Regular ferry service will resume Monday.

Source: https://torontoist.com/2017/07/hanlans-nude-beach-means-torontos-queer-community/